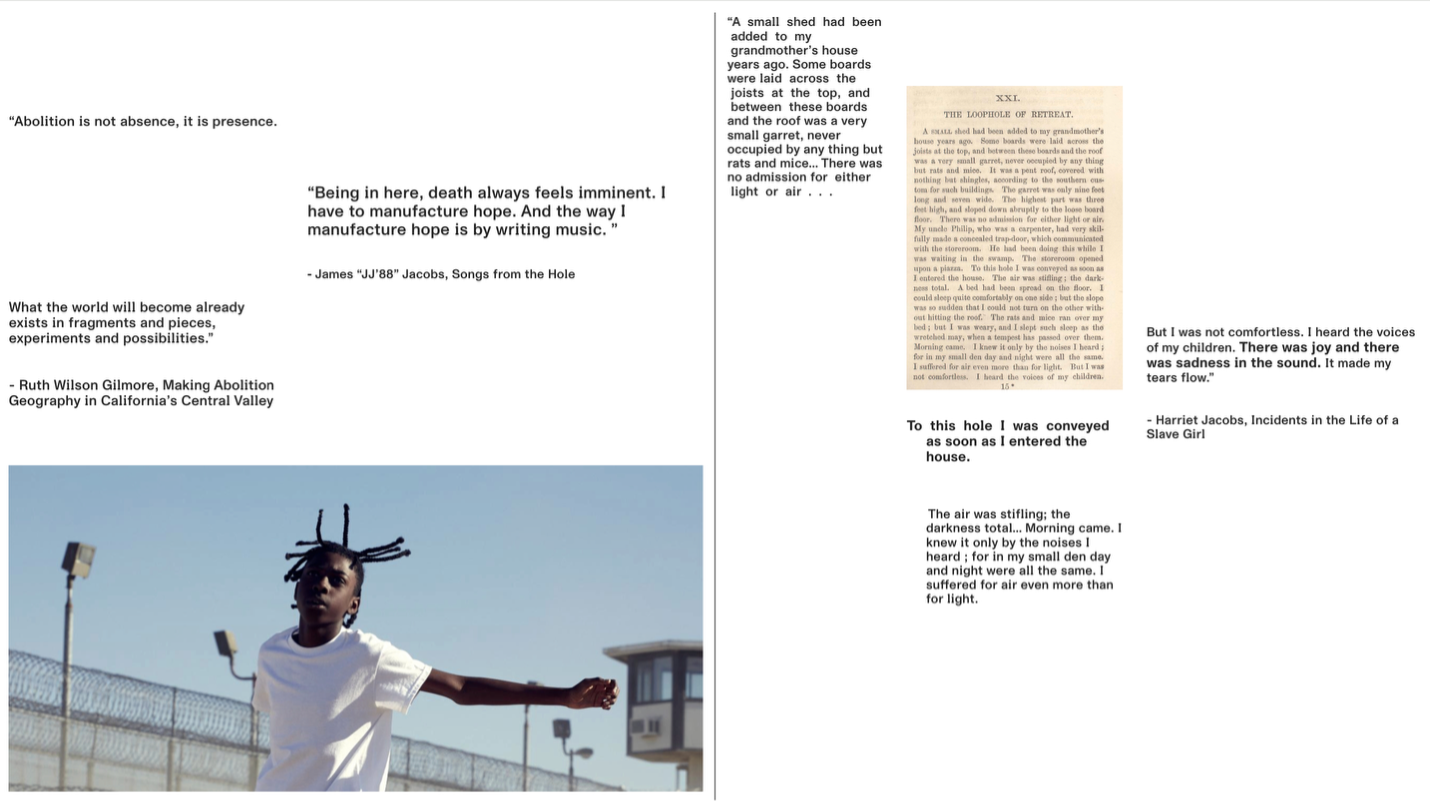

In the early 1980s the California Prison System underwent what Ruth Wilson Gilmore has called “the biggest prison-building project in the history of the world.” This mirrored the United States’ exceptional climb as the country with the highest global prison population, a position it has maintained without rival. It is from this architecture of confinement and punishment that Songs from the Hole emerged, though the film itself takes place in the mind, music and relationships of its co-writer and lead character, the rapper James “JJ’88” Jacobs. Despite being in the hold of solitary, the film is sequenced through a brimming tempo of musical scenes, interviews with loved ones and observational footage.

Songs from the Hole is an acclaimed documentary-visual album composed by James “JJ’88” Jacobs while coming of age in prison. In this reflections piece, Doctoral Candidate Farrah Rahaman interviews the film’s director, Contessa Gayles, and its producer, Richie Reseda. They came together ahead of the film’s release on Netflix to discuss making films that push form and defy genre as, by and with incarcerated people. Their conversation echoes Ashon Crawley’s careful question: “What can one hear in confinement, and how can that hearing be connective lineament?”

Farrah: Let’s start at the beginning. I’ve read that you all met and started to work together through ‘The Feminist on Cellblock Y’, a documentary produced for CNN about a feminist study collective developed by Richie and other incarcerated people. Can you talk about building a friendship through this first project, and the early seeds of Songs?

Richie: I met 88 about a year after he wrote the music at the center of Songs from the Hole. He transferred to the prison where I was at, and I had recently released an album there. We had the opportunity to produce and record the original version of these songs while we were in prison together, and during that time we were working on that we met Contessa, who was coming in to do The Feminist on Cellblock Y. We wanted to do a visual album, and we asked Contessa if she would direct it. To the benefit of us, she said, yes.

Contessa: When I came in to film the The Feminist on Cellblock Y, it was while I was working for CNN. I met Richie while he was leading these anti-patriarchy workshops for the group he co-founded, where 88 was a co-facilitator and participant. I got to see how impressive and impactful 88’s story was on the guys around him when he shared it.

It was the last day of filming that documentary – which was actually Richie’s last day in that prison before being transferred to finish his sentence elsewhere – that I got to see them play the music. Richie had the prison rental keyboard on a trash can in the corner of the gym, and 88 was singing and rapping. There was a group of their friends gathered around, and they knew all the lyrics. I was struck by how talented they were and how beautiful the storytelling was in 88’s music. I didn’t really think anything of it, besides it being a nice touching moment.

It ended up being in the epilogue portion and the credits of The Feminist on Cellblock Y. And I don’t think any of us had any notion that, fast-forward a year after that film came out, we would be embarking on this collaboration with each other, the three of us. And that we would be taking it from this more traditional space of filmmaker and film participants to collaborators in the way that we are on Songs from the Hole. That was completely natural and necessary to the film.

Farrah: I want to uplift the visual and musical language you found in this project. You describe it as a ‘documentary visual album.’ How did you land on a style? Tell me more about crafting such an abundant visual language.

Richie: Our initial inspiration was Lemonade by Beyonce, which we had effectively smuggled into prison, and we’re studying and doing workshops around. Me and 88 were both really inspired by it. And our idea was in between music videos to have documentary elements that told him and his family’s story.

Contessa: We wanted to build this narrative that’s telling this coming-of-age story starting in childhood, leading up to the incarceration years, and culminating with meeting the man who killed his brother in prison. To make the concept work it had to feel like it was one cohesive story, and that the music video and visual album elements were adding to the nonfiction and vice versa. So, we were filming the music videos, one per month, over the course of a year. And in that time, we were also filming the nonfiction elements – the interviews with 88’s family as things were unfolding for him, recording the phone calls with 88 over the prison phone line that would become the narration for the film. A lot of what I was learning was working its way back into the music video treatments through the process of writing and rewriting.

Visually we wanted to make a distinction between when we were in 88’s internal world, and when we were in the external world, so there were the pieces of the film that were of 88 and then the pieces of the film that were about him. When we were in visual album territory, we used the cinemascope aspect ratio to kind of signal that. We wanted it to have this warped, dreamy feel to it.

In terms of the color story, we used blue everywhere. It’s the colors of people who are incarcerated in the State of California. We take the colors from the uniforms that they wear and put that all throughout the film. But it also happened really naturally in the nonfiction world. Miss Janine was always wearing blue, Mr. Jacobs was always wearing blue. We didn’t construct that to happen. We did a color story that starts in childhood that’s quite warm and gauzy. Then, as we enter the incarceration years, it gets cool, cold, and then as we’re coming back out of it and into the spiritual freedom realm it warms up again.

Richie: The conversations that I had with Contessa early was how do we set up the visual language of the film. We talked a lot about the color and the layering and the mixed media, so that this doesn’t feel like a quote, unquote “incarceration” documentary. We’ve just seen that so many times, and I had no interest in making something that starts all black with white text that gives you statistics and where everything is gray. I wanted it to feel vibrant.

Farrah: I’m curious about the place of embodiment and performance in the film. Representing 88. We see dance and movement of the young boys in the yard – a kind of looseness and self-emancipation, in a zone of containment. I’m thinking about the choreography of that. Where did the idea of these sequences come from, and how did you develop them?

Contessa: The concept for the final music video was always centered around this spiritual freedom and sense of community. And when we landed on the location being the prison yard, and that it was going to be a dance sequence, it was also about reclaiming that space for community, and making it feel like the place of spiritual freedom. Because we didn’t know if and when 88 was going to come home. He was incarcerated the whole time that we were in production and into post-production. So the way that we conceptualize the structure of the film was to land in this place of the spiritual freedom, whether or not he got his physical freedom from prison and so that was always going to be the ending of the film.

We worked with an amazing choreographer named Mike Tyus, who choreographed these movements that embodied those themes of spiritual freedom, of community, of the looseness that you’re describing. And he was amazing at getting us choreography and teaching it to the cast, who were all non-dancers. There were several takes that were non-choreographed, where he did practice with the actors on how to do free movement. Those takes were the ones that we ended up using throughout the film.

Contessa: We thought of making 88 feel present and embodied in the film, despite the fact that he’s never shown on camera until the end of the film when he’s released. He’s portrayed through the actors, and his voice is heard and the music is heard. And there’s archival [footage]. But you never actually see him in person on camera until the scene where he’s released. And so we had to think of ways to make him feel present and embodied so that he could lead us through the film as the protagonist. But also to have that live alongside the fact that the audience is experiencing him in a similar way as his family and loved ones, which is at a distance and primarily over phone calls and letters.

Farrah: I had the pleasure of catching the film in various settings, where in each one you all partnered with a community organization in the city to do fundraising and awareness work around incarceration. Tell me about that approach.

Contessa: The strategy was, wherever we did a festival screening we would also do an impact screening for the community. Whether that was in outside community settings with partners who worked with folks that are directly impacted by either incarceration or community violence or state violence, or with the festivals themselves. We did San Quentin Film Festival, which was the first festival in a prison, the Sing Sing Festival, where we won the jury prize, which was by an all-incarcerated jury.

Richie: Our intention was for this film to be a tool for freedom and for people to live in a way that leads to less violence. Community violence, state violence, less incarceration, less gun violence. In Philly, we worked with the Abolition Law Center to do our screening there. We were in 30 prisons over the course of the last year in all these different cities from Hawaii to Denver.

The film is available on all the tablets to all people incarcerated in state prisons as a part of a curriculum with an organization called Healing Through Creative Practice. When people watch the film, along with two other films that form part of that curriculum, they get a week off their sentence. It was a question of “how do we use this to build as much freedom as possible and build the world anew?” Not just have a movie about a moment that pushed us towards it.

Farrah: Were there other incarcerated or formerly incarcerated people who worked on the project?

Richie: Yes, we hired as many directly impacted people as we could. So all the people who played incarcerated folks on screen, except for two, were formerly incarcerated. Two of them were actors who we found in traditional ways. Even Devonte who plays the older version of 88, we were locked up with his brother, but we found that out on location. We didn’t know that when we hired him. We know that there are impacted people who are the best of the best at their crafts.

Contessa: And also just to shout out, Antoine Banks. He is the person who filmed 88 actually getting out of prison, which happened so fast that neither myself nor Richie were even around to make it there and to capture that. I really question how that filming would have come out if it was not in his hands.

Richie: Banks himself was incarcerated for like 13 years, I think. And he drove down two hours to not only film 88 getting out, to pick up 88 and sign him out of prison. Because 88 got released so quickly that his family wasn’t there, we weren’t there, and Banks was the perfect person to know how to navigate the process, to get 88 out, to go find a place to set up a shot, and to get that freedom scene.

Farrah: I’m thinking too of “manufacturing hope through music” as 88 describes. How are you keeping hope alive these days? I know, at least for me, it’s a day by day thing.

Richie: Hope is such a choice. It’s something that I just choose whether it feels good or not. It’s not something that always feels good, actually, sometimes it really hurts. And these are not the most difficult conditions that I’ve had to live in. Nor am I living the most difficult conditions that anybody is living in right now. So I also feel a sense of duty to remain hopeful and work towards a future worth having for all of us, because I actually have a tremendous amount of leisure and rest and capacity and privilege with which to do so.

My hardest days are behind me, and I’m grateful for that. And that’s not true for many people I love, and that’s not true for many people on this earth who are being incarcerated, or genocided, or forced out of their homes, or living outside.

Farrah: We’re dealing with the slipperiness of time and reckoning with the time we have on this earth. Are there any lessons or reflections you have about the nature of time from this project?

Richie: I was just tripping out about time today, because I truly did not expect to live this long, and the idea that I could potentially live to be an elder one day is mind blowing. But I’m committed to it. Just as I witness my friends come home from prison. It gives me so much more grace for what my life has been. As hard and as crazy as things seem right now, I think a lot about my ancestors that survived middle passage, that survived enslavement all the way up to my grandfather, who’s still alive and who was a sharecropper. I was just hanging out with him recently I made him watch Sinners, which he was cool with until the vampires popped up. I just think about the conditions through which my ancestors chose hope and chose to even have children to the point where I am now alive. I got it easier than anybody who shared my name.

Contessa: I just think about our ancestors who already laid the blueprint for us in times like these, in times as dark as these, and in times that have been darker than these. This is when we have to work as artists. To bring Toni Morrison in, this is the time where we go to work.

Songs From the Hole is available to stream on Netflix. Learn more here.

Contessa Gayles is an award-winning film director, writer, DP, editor and an Emmy-nominated producer. She brings intimacy and artistry to stories of identity, community, coming-of-age, liberation and the radical imagination.

Richie Reseda is a music, film and content producer who was freed from a California prison in 2018. He co-created and co-hosts the Spotify Original podcast Abolition X. While in prison he started Question Culture, an independent media collective that houses his projects. He co-founded Success Stories, the feminist program for incarcerated men chronicled in the CNN documentary The Feminist on Cell Block Y.

Farrah Rahaman is a doctoral candidate at the University of Pennsylvania and a cultural worker whose inquiry and meaning-making processes are activated through a scaffolding of scholarly research, cultural organizing, curation and filmmaking. Farrah’s interdisciplinary methodology centers women’s narratives, political and social imaginations, and visual culture.