Museums, galleries and memorial sites are increasingly under attack from political groups attempting to reshape public memory and erase uncomfortable histories. In Chile, one of the presidential candidates publicly announced his intention to close the Museum of Memory and Human Rights if elected, accusing it of spreading hate and dividing the nation. In the United States, some of the country’s most prominent cultural institutions have been denounced by the president as dangerous vehicles of revisionism or in the case of the “Trump-Kennedy Center”, experienced a hostile takeover. In Thailand, the exhibition Constellation of Complicity: Visualising the Global Machine of Authoritarian Solidarity, which critically examines authoritarian power in Asia, was censored under political pressure from the Chinese government.

Across different geographies, eras and political scenarios, institutions of public memory have been accused of being “one-sided histories,” “rewriting the past” or politically biased when they do not align with the visions of the prevailing power. These attacks differ in context and scale, but they share the same logic: the institutions that keep memories alive are a threat to hegemonic powers. The weakening of institutions that safeguard collective memory represents a twofold threat to democratic societies: First, by implementing hostile cultural policies, and second, by reducing the public’s ability to understand its past and identity.

The aforementioned cases in the United States, Chile and Thailand also point to broader patterns through which control over historical narratives becomes a tool of political power. When authorities or political actors attempt to discredit, censor or even dismantle institutions of memory, they are actively reshaping the conditions for publicly discussing the past (and, as a consequence, the present and future). In this moment of increased risk to cultural memory, it is important to understand that museums and sites of public memory are increasingly contested terrain rather than spaces of consensual heritage. This report examines the political risks faced by museums and sites of memory today, analyzing why they have become targets of suspicion, censorship and delegitimization, and what these attacks reveal about the role of memory in democratic societies.

Memory, power and institutions: Why is memory political?

Before getting into the complexities of why memory institutions are increasingly at risk, it is important to acknowledge that memory is not a neutral record of the past or a factual archive that societies simply decide to preserve or neglect. Memory is a socially produced, selective and contested process. What we remember as a community or country is shaped by power relations, institutional frameworks and the political needs of those in charge. In other words, what a society remembers is determined by social forces that determine which stories are emphasized and which ones are minimized, often reflecting the power interests of those who have the authority to define what the “official memory” should be.

If memory is strategically curated, then the places that collect and present memory (such as museums, archives, memorial sites, historic buildings or memorials) become spaces where political power is played out. Collective memory, or what people remember as members of a group (Halbwachs, 1992), depends on institutions that can organize, present, transmit and legitimize to the public shared narratives about the past (J. Assmann, 2013). Museums and archives help turn individual experiences into lasting public records, often transforming personal stories into collective recognition, so that events such as violence and suffering are remembered beyond private grief or family memory.

However, these institutions do not only preserve the past; they also actively shape how the past is interpreted and taught to future generations. For this reason, they have a central position in political struggles over meaning and national identity. Political attacks on memory institutions can be justified through claims of bias, historical revisionism or accusations that they present only one side of the full story (Jelin, 2002). Such critiques rely on a misleading opposition between a supposed objective history and a subjective memory (A. Assmann, 2020). In practice, all historical narratives are shaped by a process of selection. As a result, when memory institutions are denounced as dangerous, it is often because they do not present the past as settled or morally neutral. These institutions can highlight situations marked by state violence (such as authoritarian rule or human rights violations), structural injustices (such as systems of slavery) or foreground marginalized experiences, thereby challenging dominant narratives that portray national history as heroic and uncontested (Jelin, 2002). In this sense, the accusations of “revisionism” by those who seek to censor memory institutions serve as a strategy to delegitimize critical engagement with the past rather than to defend historical accuracy.

Those trying to weaken or cut funding for institutions of public memory often claim that they are divisive, overlooking the fact that these institutions are a prerequisite for meaningful reconciliation (particularly in societies that have experienced periods of violence, repression or deep social division). Forcing people to forget does not heal social wounds; instead, it hides unresolved conflicts and allows ongoing harms to remain unspoken.

When institutions that document and interpret past violence are weakened or shut down, societies lose crucial spaces where they can debate about their past, acknowledge victims, make perpetrators of violence accountable for their actions and acknowledge injustices. More broadly, this threatens democratic life because people have fewer opportunities to engage critically with the past and develop an understanding of their past and therefore their identity.

Global attacks on memory and institutions

The attacks on memory institutions in the United States, Thailand and Chile are not confined to specific political systems or regions. Across different parts of the world, institutions dedicated to preserving and interpreting collective memory have become targets of coordinated political interventions that seek to control how the past (and the present) is narrated and publicly discussed. While the forms of these attacks vary, they follow recurring patterns that reveal how museums, exhibitions, archives and sites of public memory are increasingly positioned as obstacles to hegemonic powers. The following case studies highlight common strategies used to undermine memory institutions and the context in which these attacks unfold.

Case 1: Chile and the Museum of Memory and Human Rights

In Chile, the Museum of Memory and Human Rights has often been attacked by political groups who argue that remembering past violence harms national unity and Chilean identity. Inaugurated in January 2010, the museum seeks to acknowledge and draw attention to the violence committed during Augusto Pinochet’s military dictatorship between 1973 and 1989, including the forced disappearance of people for political reasons. Over the years, it has gained international recognition for promoting human rights and democratic values and has become a central part of Chilean collective memory.

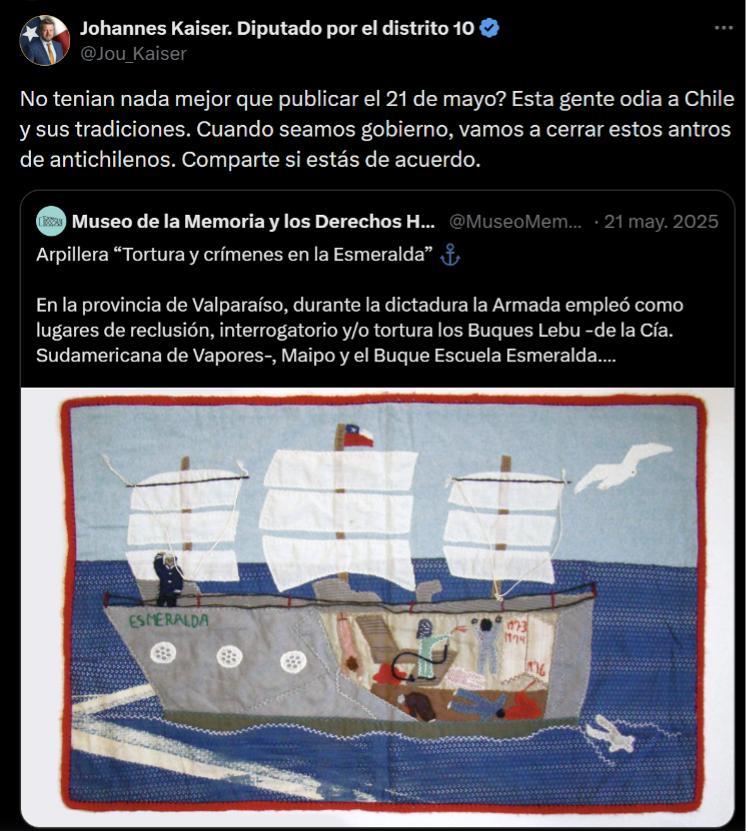

During the 2025 presidential campaign, far-right candidate and member of the Chamber of Deputies, Johannes Kaiser (National Libertarian Party), publicly threatened to close the museum if he won the election, accusing it of spreading hatred and disrespecting Chilean traditions. His statements were triggered by a social media post published by the museum on Navy Day, which referenced documented cases of torture that took place aboard La Esmeralda (an iconic ship in Chilean naval history) during the dictatorship. In response, Kaiser denounced the institution as being anti-Chilean and hating on the country’s history and traditions.

Although Kaiser lost the election and his threats never materialized, another far-right candidate, José Antonio Kast, was elected. While Kast has not yet publicly commented on the museum, his political movement is associated with the dictatorship’s values and ideas, raising questions about the future of the Museum of Memory and Human Rights and other institutions dedicated to preserving public memory in Chile.

These attacks are not unprecedented. In 2018, Mauricio Rojas (then Chile’s Minister of Culture) publicly dismissed the Museum of Memory as a “montage” designed to manipulate emotions and distort history, describing it as a “shameless and deceitful use of a national tragedy”(BBC News Mundo, 2018). Such statements echo broader strategies of delegitimization, in which memory institutions are accused of emotional manipulation, bias, or historical falsification to undermine their credibility and justify their marginalization.

Even when these critiques do not result in tangible censorship, they reveal how memory institutions become targets precisely when they challenge heroic or sanitized national narratives. By recalling state violence associated with symbols of national pride, they framed the museum as disrupting dominant commemorative frameworks and exposing unresolved historical tensions in the country. Rather than engaging with the documented facts presented across the museum’s exhibitions, political actors presented the institution’s work as an attack on the nation itself, positioning critical remembrance as incompatible with patriotism.

Case 2: United States, patriotism and the rewriting of national history

In the United States, cultural and memory institutions have increasingly been drawn into political conflicts over national identity, patriotism and the interpretation of history. Since the start of the second Trump administration, several of the country’s most prominent museums and cultural institutions have been publicly denounced by the president as dangerous vehicles of “revisionist” history, accused of distorting the nation’s past and undermining American values and legacy, such as contributing to “advancing liberty, individual rights and human happiness” (The White House, 2025a). These attacks intensified in response to exhibitions, educational programs and public statements that addressed histories of slavery, racism and structural inequalities, which the administration has accused of dividing American society and fostering a sense of national shame that disregard the country’s progress.

One of the government’s first attacks on cultural memory took place in March 2025 with the executive order “Restoring Truth and Sanity to American History.” The order denounced a supposed effort to rewrite the nation’s history, replacing objective facts with distorted narratives driven by ideology rather than truth. In the following months, museums, exhibitions, and memory sites were accused of revisionism and pressured to modify their displays to reflect the government’s vision of what “America really is”(The White House, 2025a).

In August 2025, the White House sent a letter to the Smithsonian Institution, requesting a review of all exhibition materials to ensure they removed any “divisive or partisan narratives” and instead “reflect unity, progress and the enduring values that define the American story” (The White House, 2025b). This directive came in the context of the country’s soon-to-be 250th anniversary, a moment intended to celebrate the nation’s achievements. As the letter notes, America “will have no patience for any museum that is diffident about America’s founding or otherwise uncomfortable conveying a positive view of American history” (The White House, 2025b), remarking on the intentions to leave out anything that could damage the country’s public image.

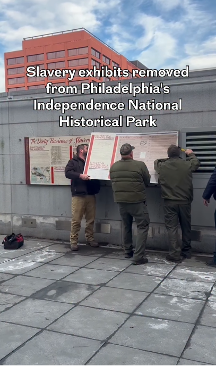

One of the latest acts in this revisionist movement is the removal of a slavery memorial at the President’s House in Philadelphia, an exhibit that opened in 2010 to honor the nine individuals enslaved there by George Washington. It is the only federal historic site that commemorates the history of slavery in the country. The National Park Service was instructed in late January 2026 to begin removing the panels, sparking a negative reaction from the public and the local government, which filed a lawsuit in federal court to have the signs put back.

These interventions have been framed by the government not as acts of censorship but as efforts to defend “true” or “patriotic” history. Institutions that highlight racial violence, systemic injustice, or the experiences of historically marginalized communities are being portrayed as politically biased or ideologically driven, allegedly imposing a negative or divisive interpretation of the national past. In this context, critical engagement with historical violence is recast as an attack on national unity and social cohesion. By framing certain historical interpretations as illegitimate or harmful, these attacks seek to narrow the range of narratives deemed acceptable within public institutions and educational spaces.

The United States case illustrates how accusations of “revisionism” can be used as a political tool to discipline memory institutions. When delegitimizing critical historical work as unpatriotic or divisive, political actors reassert control over national narratives and limit public confrontation with unresolved legacies of violence and inequality. Ultimately, these attacks undermine the capacity of memory institutions to serve as spaces for democratic debate, historical accountability and pluralistic engagement with the past.

Case 3: Thailand and an episode of transnational censorship

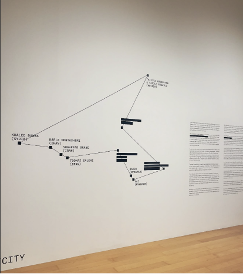

Constellation of Complicity: Visualising the Global Machine of Authoritarian Solidarity is a contemporary art exhibition that opened in Bangkok in July 2025 at the Bangkok Art and Culture Center, with the aim of exposing how authoritarian governments, including China, Russia and Iran, collaborate to maintain control and suppress dissent. By mapping these transnational networks of repression, the exhibition framed artistic practice as a form of critical memory, connecting local experiences of violence to broader global structures of power. It was precisely this critical intervention that later made the exhibition a target of political censorship, showing how attacks on memory and cultural institutions can extend across national borders.

Three days after the exhibition opened, representatives from the Chinese embassy, along with Bangkok city officials, visited the venue and demanded that it be shut down. The Chinese authorities complained about works by Tibetan, Uyghur and Hong Kong artists and initially demanded that the exhibition be closed. Although it remained open, the names and origins of several artists were covered with black paint, visibly censoring the works and altering how the public could understand them. Some news agencies have reported that even some of the monitors that displayed videos are now turned off. The consequences extended beyond the exhibition space itself. Fearing retaliation, some artists felt forced to leave the country. One Myanmar artist whose work was included in the exhibition fled Thailand and is now seeking asylum in the United Kingdom, citing concerns for his safety.

These actions were justified by claims that the exhibition promoted separatism and misrepresented history, and that it threatened the diplomatic relationships between the countries involved. The Chinese embassy stated that the exhibition “disregards facts,” misrepresents China’s policies in Tibet, Xinjiang and Hong Kong, and harmed the country’s “core interests and political dignity”(Wong, 2025). These accusations, like in other cases, use the idea of historical accuracy and national sovereignty to delegitimize critical engagement with state violence. However, the censorship drew international attention. As news and social media posts denouncing the restrictions went viral, more visitors wanted to attend the exhibition, sparking debates about artistic freedom and helping prevent it from disappearing into obscurity.

This case shows how memory and cultural institutions can be pressured not only by domestic authorities but also by foreign governments seeking to extend their political influence. When external power shapes what art can be displayed and which histories can be publicly acknowledged, cultural autonomy is seriously undermined. This case illustrates how attacks on memory institutions increasingly operate across borders, shrinking the space for critical remembrance and public debate far beyond the confines of a single nation.

https://www.instagram.com/p/DNRPtuzTb3a/

Recognizing patterns in memory attacks

The cases discussed in this report reveal how attacks on memory institutions take different forms depending on the historical context, political orientation and local conditions in which they occur. The actors involved, the intensity of the attacks and their material consequences vary from place to place. Despite these differences, it is possible to identify recurring patterns that help illuminate how contemporary attacks on memory operate and what forms they are likely to take. Recognizing these patterns is crucial if we are to respond to attacks on institutions preserving cultural memory before lasting damage is done.

1. Memory is tolerated if it serves national pride

One recurring pattern among these cases is that memory is preserved and celebrated only when it reinforces an idealized image of the nation. In this view, national history is imagined as unified, morally coherent and oriented toward progress, with all actions framed as having been carried out for the good of the nation. Histories that introduce rupture, responsibility or moral ambiguity, particularly those that foreground state violence, injustice or exclusion, are seen as threatening and incompatible with the narrative political actors seek to maintain. As a result, there is little room for critical reflection or public debate about the past, and even less space to ask what lessons might be drawn from historical violence to prevent its repetition. Although those who attack memory institutions often claim to be defending unity, harmony and a shared national identity, their actions frequently produce the opposite effect. By marking certain interpretations as “unacceptable” or “anti-national,” they deepen polarization and provoke resistance from those who seek to defend memory as a public and democratic value. In this sense, attempts to enforce a single narrative of the past tend to fracture, rather than unify the social fabric.

2. “Revisionism” as a delegitimizing weapon

Another clear pattern is the use of “revisionism” as a tool to discredit memory institutions. When Chilean politicians describe the Museum of Memory as emotional manipulation, when United States authorities accuse museums of ideological dogma, or when Chinese officials claim that an exhibition disregards facts, they all rely on a false opposition between “objective history” and “biased memory.” In practice, these accusations do not serve to defend historical accuracy. Instead, they delegitimize critical interpretations of the past that are grounded in extensive documentation and empirical evidence. Labeling memory work as revisionist becomes a way of diminishing what is perceived as politically threatening, pushing certain narratives to the margins and ensuring that uncomfortable voices are not heard. In this sense, revisionism operates less as an intellectual critique than as a form of political intimidation.

3. Censorship in all but name

These attacks share a common reliance on indirect or disguised forms of censorship. Threats to close institutions, reviews of exhibition materials, executive orders, funding pressures and diplomatic interventions are all mechanisms through which memory can be controlled or silenced. Yet these actions are rarely framed as censorship at the moment they occur. Instead, they are presented as administrative decisions, efforts to restore balance or measures taken in the name of objectivity. It is often only after media attention or public mobilization that these interventions are recognized for what they are. By that point, however, the damage may already be difficult to undo. This highlights the importance of naming censorship early, before it becomes normalized or irreversible.

4. Memory institutions framed as political actors

Finally, across the cases examined here, memory institutions are repeatedly treated as political actors accused of “taking sides.” Museums, archives, memory sites and cultural spaces are portrayed as “partisan” when they want to highlight and denounce histories of violence, exclusion or inequality. Yet their work is not about advancing a political party or an ideological agenda or partisan position; it is about opening space for critical remembrance, historical accountability, and plural interpretations of the past.

The aforementioned accusations rely on a false equivalence: that acknowledging structural violence or marginalized experiences is something inherently political, while narratives that are considered celebratory or patriotic are “neutral.” In reality, all historical narratives involve interpretation and selection. The difference is that dominant narratives are presented as neutral, objective or beyond dispute. It is when memory institutions challenge these narratives that they are accused of bias. As a result, labeling memory institutions as political actors acts as a strategy to discipline them. By accusing them of activist partisanship, political authorities delegitimize their work, justify interventions, enforce strict oversight and even reduce funding. The conflict, then, emerges because these institutions insist on acknowledging the complexities, refusing to simplify the past into unified narratives of pride and harmony. . In these moments, memory itself becomes the target, not because it is inaccurate, but because it refuses to be silent.

How can we defend memory?

Attacks on memory institutions are attacks on us, our history, and the ways we act collectively. They matter because memory is essential for democratic societies: it allows people to be informed, reflect on the past and make decisions knowing the history that shapes their present and future. Now that we have identified the risks and patterns of these attacks, what can we do? There are limits to what regular citizens can accomplish directly, but we can promote protections, stay vigilant and support actions that make it harder for memory to be silenced.

1. Memory institutions need more autonomy

The protection of collective memory requires shielding museums, archives and cultural spaces from political interference. Even if institutions are financed and overseen by governments, governance structures must protect them from retaliation. Without such protections, they remain vulnerable to censorship disguised as administrative oversight, budget cuts or bureaucratic decisions.

In the United States, political pressure on cultural institutions has prompted public mobilization. When the government attempted to reshape cultural programming at the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, artists and performers denounced these actions as threats to artistic and institutional independence, publicly withdrawing or refusing to participate. While these acts of refusal have not solved the structural problem on their own, they have generated public debate, media coverage and scrutiny by the audience. They have made visible what might otherwise have been framed as routine administrative change.

What can we do? We can advocate for laws, policies or boards that guarantee institutional independence. For example, we can support transparent appointment processes for directors and curators that limit partisan control. We can stay informed and monitor emerging threats, giving them public visibility so authorities cannot act without scrutiny. We can engage with local representatives, and support professional organizations of historians, archivists, curators, or human rights groups that defend institutional autonomy. Public pressure does not replace structural reform, but it can deter opportunistic interference and strengthen the case for long-term protection.

2. Naming censorship early and publicly

As discussed earlier, it is crucial to call censorship what it is, even when it appears indirect. Early public framing matters. Journalists, scholars and civil society play a central role in this process by reporting, analyzing and publicly challenging attempts to silence or reshape memory. Because contemporary attacks on memory rarely present themselves openly as censorship, one of the most effective strategies is to name and contest these interventions early, before they become normalized or administratively irreversible.

This can take many forms. Scholars can write articles or blog posts that contextualize these attacks and explain why they threaten public memory and democratic life. Journalists can cover controversies over exhibitions, museum policies or removals of historical markers to draw public attention before changes are implemented. The public reaction against censorship in the President’s House in January 2026, shows that journalists, scholars and individuals with public platforms can make a difference here. What might have been framed as an interpretive update by authorities became a matter of public concern when journalists, historians and community members raised questions about the implications of minimizing slavery at a site symbolizing American freedom. Public scrutiny through news articles and social media posts reframed the issue as a broader question about how national heritage sites narrate uncomfortable histories.

Civil society organizations can mobilize public campaigns, petitions or social media advocacy to highlight the risks and pressure decision-makers to halt or reconsider interventions. Even individual citizens can play a role by attending threatened exhibitions, visiting archives, engaging with public debates, or raising awareness among their networks. In Philadelphia, when the panels addressing the history of slavery were removed or altered, some community members printed copies of the original text and temporarily posted them in the spaces where the panels had been displayed. Others turned to social media to document and circulate what was happening, ensuring that the change did not go unnoticed. These actions transformed what might have remained an internal interpretive decision into a visible public controversy. By documenting and publicly contesting the removal, citizens disrupted the normalization of the intervention and asserted that historical interpretation at national heritage sites is a matter of democratic concern, not administrative discretion.

3. Memory as a democratic practice, not a cultural luxury:

Finally, memory is not just about preserving the past, it is a tool for accountability, recognition of harm, and public debate. Thus, defending memory is not only a matter of cultural heritage, but it is also a democratic imperative. When societies lose spaces to critically engage with their history, they also lose the tools to confront injustice, acknowledge victims and debate the values shaping the present and future. Here is where individuals come in. We can actively participate in museum exhibitions, memorials, or archives that explore contested histories, especially those addressing state violence, structural inequality or marginalized experiences. We can advocate for the protection of spaces where memory is critically discussed, emphasizing their role in democratic life rather than merely as cultural heritage. For instance, after Chinese authorities exerted pressure to censor the Constellation of Complicity exhibition in Indonesia, there was a surge in public attention. Visitors flocked to the exhibition in response to news and social media posts highlighting the censorship, ensuring the works were seen and discussed. In this case, the active engagement of audiences not only countered attempts at silencing but also reinforced the exhibition’s role as a site of critical reflection on transnational power and repression. Similarly, in Chile, the Museum of Memory continues to draw large numbers of visitors despite repeated political attacks, and other institutions such as Londres 38 serve as enduring spaces where historical memory and critical reflection are preserved. In these cases, the active engagement of audiences not only counters silencing but also strengthens the impact of memory institutions as sites of critical reflection, democratic dialogue and public accountability.

References

Assmann, A. (2020). Is time out of joint. In The Rise and Fall of the Modern Time Regime (pp. 92–147). Cornell University Press.

Assmann, J. (2013). Communicative and Cultural Memory. In P. Varga, K. Katschthaler, & D. Morse (Eds.), The theoretical foundations of Hungarian “lieux de mémoire” studies (pp. 36–43). Debrecen.

BBC News Mundo. (2018). Chile: El polémico comentario sobre el Museo de la Memoria por el que tuvo que dimitir el ministro de Cultura Mauricio Rojas. BBC News Mundo. https://www.bbc.com/mundo/noticias-america-latina-45176804

Halbwachs, M. (1992). On Collective Memory. University of Chicago Press. https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226774497.001.0001

Jelin, E. (2002). Los trabajos de la memoria. Siglo XXI de España Ed. [u.a.].

The White House. (2025a). Letter to the Smithsonian: Internal Review of Smithsonian Exhibitions and Materials. The White House. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/2025/08/letter-to-the-smithsonian-internal-review-of-smithsonian-exhibitions-and-materials/

The White House. (2025b). Restoring Truth and Sanity to American History. The White House. https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/03/restoring-truth-and-sanity-to-american-history/

Wong, T. (2025, August 15). How a Bangkok art show was censored following China’s anger. Bbc.Com. https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cj6yx71565jo