Documentaries tend to rely on digital evidence to speak for those who often can’t or won’t. Certain digital technologies and their proliferation have led to even the most covert professionals leaving traces of their actions and ideologies online—allowing media practitioners to search and scrape different parts of the internet for digital artifacts in pursuit of truth and transparency. This practice carries its share of legal risks, financial costs and technological complexities for investigative film producers, who must often wade through many gigabytes of data to find the germ of a story. A documentarian must negotiate not only what to say, but also what to leave unsaid, as revelations can jeopardize networks and bring to light systems of power that can harm.

In The Family Statement, directors Grace Harper and Kate Stonehill present a 15-minute compilation of Whatsapp messages sent between members of the Sackler family between October 2017 and June 2019. In this reflection, Center for Media at Risk doctoral fellow Muira McCammon talks with Harper and Stonehill about the documentary and their process of weeding through the many digital artifacts related to the Sacklers and Purdue Pharma, which faced criminal charges for its documented involvement in the opioid epidemic.

Can you talk a bit about how you first became interested in the Sackler family, and what led you two to undertake this collaboration?

We were motivated to make this film after facing the effects of opioids in our own families. As co-directors, we both have family members who have struggled with substance use disorder. When others shared their stories with us, we empathized from a personal perspective, having witnessed the pain and complexity of substance use disorder firsthand. In making this film, we wanted to reflect the confusion and uncertainty that we’ve lived with and bring it into dialogue with the vehement efforts to control the narrative expressed in the Sackler family Whatsapp messages.

We started this film with a hope that it could be part of an ongoing dialogue about changing the way we discuss substance abuse. There is so much research that shows that the more we see stereotypes on screen, conscious or unconscious biases are reinforced – and yet in fiction and non-fiction we often see the same stories of substance abuse told, one of a hero’s journey of rock bottom and redemption. We both believe that creative non-fiction can play a role in challenging these stereotypes, because they have consequences for the way the general population sees people that struggle with this disease. We made this film to explore the many other possible storylines that can be told about substance abuse, and to bring in an analysis of the systemic forces at play.

The Family Statement weaves together video footage of congressional testimony by different members of the Sackler family as well as the verbiage of WhatsApp messages they exchanged. At this point, there has been so much media generated by and also about the Sacklers. How did you weed through it all and figure out what belonged in the documentary?

We began the film with a shared desire to explore pharmaceutical companies’ role in overprescribing opioids. At the time, protests to remove the Sackler name from institutions were gaining traction, and we felt doctors would be an interesting starting point for examining the role that big pharma played. We read online about an innovative addiction treatment program that was being piloted in California. We made contact with those running the program and built trust through weeks of phone calls and, eventually, in-person discussions with press officers and representatives from the UC Davis Medical Center Addiction Treatment Program. We negotiated hard-won access to the UC Davis Medical Center Emergency Room — a place that has never before allowed cameras inside to film or photograph the medical professionals at work. We traveled to Sacramento for our first shoot in May 2019.

We were captivated by the medical professionals and first responders who we met during this shoot. Our plan was to secure additional funding and then return to Sacramento, to film over a longer period with the people who we’d now identified as our primary contributors. When the pandemic arrived, however, it became clear that traveling to California for emergency room shoots was going to be impossible.

While we were confined in our houses during months of lockdown, we returned to our original intention for the film. We went back to our research; at this point, we were aware that Purdue Pharma had been embroiled in bankruptcy proceedings, which we were following closely. In coverage of the case, we read that a Sackler family Whatsapp group chat had been included as part of these proceedings, meaning that the document containing the Whatsapps was technically public.

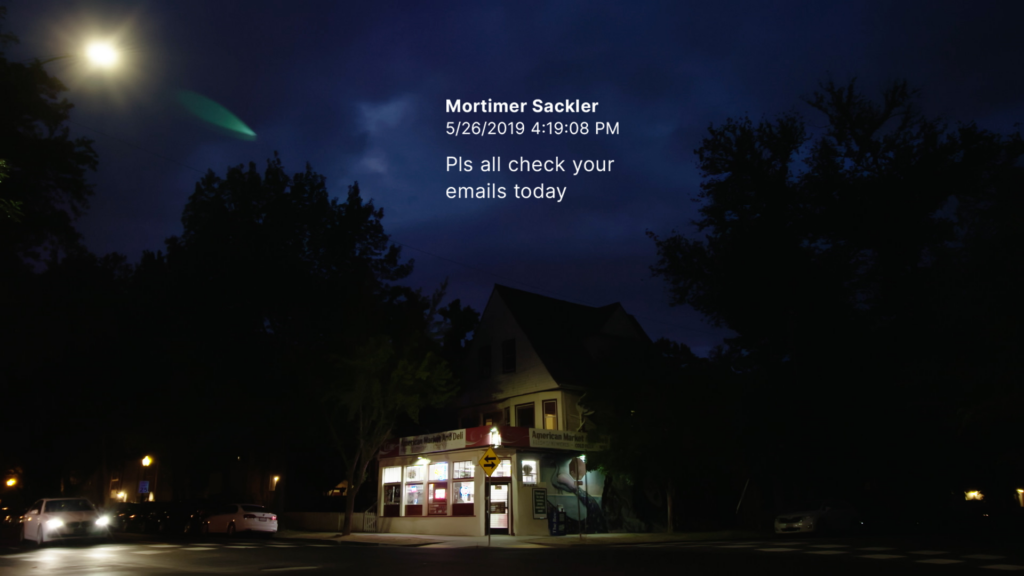

We were intrigued by what these Whatsapps would say – what they could tell us about how the Sacklers were engaging with the question of their own role in the crisis. It felt like exploring this returned us to our initial intentions for the film: to look at accountability in the context of the crisis. We spent hours on PACER – a database for court records – sourcing these Whatsapps, and eventually found them.

We felt these Whatsapps would make a compelling, poignant film. We were also excited by the idea of working with source material that had never been made publicly available to a wide audience before. We began a process of editing these Whatsapps into a script. In an open-ended, experimental creative process, we would send Premiere Pro projects back and forth (we edited the film ourselves), playing with different ideas of how the various elements would interact. In the end, we landed on a juxtaposition of different elements that had been present throughout our process (interviews, verite footage, the Whatsapps).

I am also thinking about the challenges that arise in telling stories about collectives of people and specifically powerful, wealthy families. I’m thinking of different efforts over the years to investigate the British Royal Family, the Murdochs, the Madoffs, the Trumps, the Kochs and, even more recently, the Murdaughs. Can you talk a little bit about the process of weaving together a narrative about the Sacklers? How did you determine, for example, which family members to include in the documentary and which to leave out? Was it ever tempting to focus on a single Sackler instead of the family as a whole?

Our process was very much guided by the content of the Whatsapp group chat. When we edited a script together out of the messages, we allowed ourselves to be led by what we felt was working narratively and editorially, rather than seeking to include or exclude certain family members. We were aware that the different members of the family have different relationships to Purdue Pharma, and we felt there was an interesting opportunity to reflect this nuance through including one of the messages where it is referenced in the chat (10/27/2017 3:47:05 PM Elizabeth wants the family and Purdue to make a statement that the Arthur side of the family has never had any involvement with Oxy and has not benefitted financially)

We also made efforts in the way that we edited the messages together, to portray the Sackler family as a family, by including intimate, familial messages that many of us can relate to (11/23/2017 11 01 15 PM Happy Thanksgiving everyone!) It is widely understood that addiction is something that is experienced by a family, so we were interested in the ways in which the Sacklers can also be understood, seen and experienced as a family. In the film, their reputational concerns are juxtaposed with the concerns of family members helping their loved ones through recovery.

I am reflecting on the role that digital artifacts—emails, texts, tweets, and the like—play within documentary films. What advice would you give other directors, who are faced with sorting through a trove of Whatsapp messages as a form of evidence?

Embracing a form that is not character-based can be daunting, but it can also be exciting in terms of the potential for impact. We found it creatively exhilarating not to center an individual, which led to an approach that allowed us to speak to the structures underlying the crisis. It’s been wonderfully rewarding to watch the audiences who’ve seen the film go on that journey, too.

In order to make it work, we engaged in a process of true experimentation, which was facilitated by the fact that we edited the film ourselves. We found the form by setting ourselves a series of rules – and of course, by a process of trial and error. For example, we decided to approach our script chronologically; we wanted to retain the original order that the Whatsapps were sent in, as much as possible. We also worked a lot on paper alongside our picture edit, transcribing the Whatsapps into scripts. This helped us to be precise about our edits, as we were figuring out how to create a narrative arc out of the messages.

At one point, the film existed solely as a series of Whatsapp messages. It was only by stripping out the other elements that we were able to distill what we needed from them, and why they were crucial to the form. So it was a very organic, instinctive but detail-oriented process of removing things and putting them back in, in order to understand how they worked together.

Brevity can pack a punch. Was the plan always to make a short-doc or did you experiment with building out a longer arc?

The experimental editing process we engaged in meant that we were able to be open in regards to length, and not have a length in mind before working through the material. We were open to a longer film, but during the edit we found a pace that could allow this constructed conversation between the three visual worlds within the film, and when we found this we made a decision that a short film would suit that language and pace.

As you dug deeper into communications inside and on behalf of the Sackler family, what surprised you most, and what have been some of the highlights for you in showing the documentary at a variety of film festivals over the past year?

We were both really struck by how removed The Sacklers were from the world that they have, in many different ways, helped to shape. It was surprising how willfully blind they were, and how much their wealth had protected them. Reading their messages in chronological order, and moving between really familiar family greetings about Thanksgiving to sharing and commenting on articles about them, you get the distinct impression that some members of the family genuinely don’t think they have done anything wrong, which is truly shocking to read.

Your documentary represents such a profound intervention in highlighting how to give a voice to the secretive, a vocabulary and a language to a family that tried to eschew and avoid visibility and accountability at all costs. It is also a meditation about reputation, networks, and institutional power. But I want to try to put it in conversation with some of the other works that have tried to shine a light on the harms enacted by the Sackler family and Purdue Pharma. Before I saw your own documentary, I also binged Dopesick. How deep did you two go in watching and immersing yourself in other stories that had already been told about the Sackler family before making The Family Statement? To what extent, if any, was it helpful to see what had already been said?

We actually began work on the film before many of the bigger projects about the Sackler family were released, so we weren’t aware of them at the time. It feels like things have materially changed, though, since we started making this film, in terms of people’s awareness of this story. The Sackler name continues to be removed from institutions. It feels like a moment of cultural reckoning. And it’s been great to see the story reverberate across geographies and reach mainstream audiences.

What is next for both of you? Any other projects on the horizon?

Grace Harper: I’m in the edit for a creative feature documentary that also explores substance abuse, through a more personal lens.

Kate Stonehill: I’m currently releasing a feature doc, Phantom Parrot (premiered in March at CPH:DOX).

As a team, we are digging into some other topics where a similar approach to The Family Statement could be a creative possibility.