The following transcript is from Cherian George’s lecture on disinformation and hate spin, hosted by the Center for Media at Risk. He spoke on October 9 at the Annenberg School for Communication, University of Pennsylvania.

The Center for Media Risk, as I understand, is a response to the sense of crisis that has gripped media and society in the United States. As a non-American from half the world away, I was frankly surprised to be invited to come as a visiting scholar at this time. Of course, intellectually, we know that it’s precisely when we need to make sense of confusing change that it’s especially helpful to cross boundaries of history and geography. But emotionally, such times tend to make most academics look inward and become more parochial. Fortunately for me, Barbie Zelizer is not most academics. So, I find myself here during interesting times. Thank you so much.

I want to talk about a subject that sadly requires no introduction. I don’t have to explain why this topic matters. In recent years, many of us have been stunned to see how boldly bigotry has strutted from the dark alley ways into the brighter sunshine of public squares in many democracies. Even in countries more familiar with communal violence, the observers point to alarming new levels of cynicism and impunity. We’re familiar with the rise of the far right in elections, the impact of populist intolerance on national politics and escalating hate crimes on the streets. What is less well understood is why these things are happening simultaneously in so many different societies.

The best writing I found on this subject convinces me that we are at a world historic inflection point, no less significant than the end of the Cold War. We’re probably witnessing the death throes of the neoliberal revolution that made most societies, even those that are nominally communist, embrace free markets as the handmaiden of social economic progress. Pankaj Mishra in this excellent book, The Age of Anger, suggests that the 1990s sparked aspirations among peoples everywhere that could not possibly be satisfied because they were based on a materialist ethic, and mindless emulation and not genuine need.

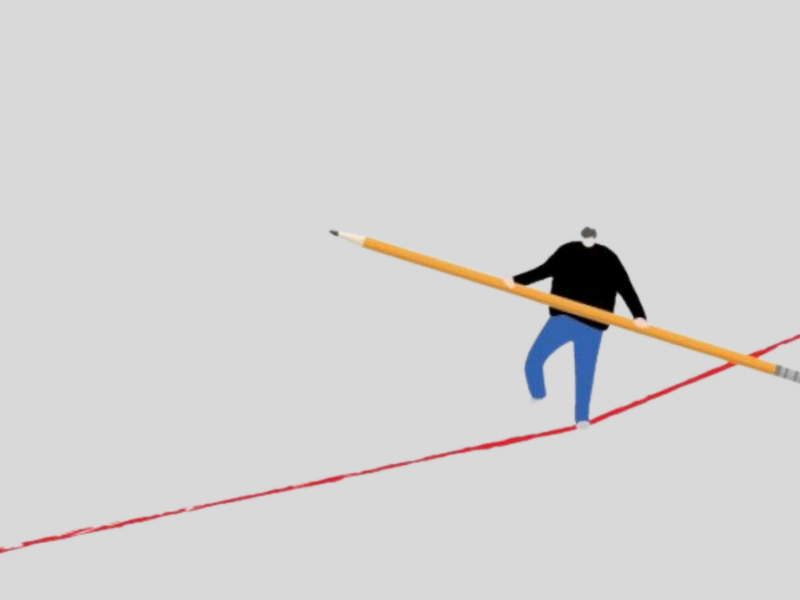

The resulting resentment–caused by a mix of envy, humiliation and powerlessness–is poisoning civil society, undermining political liberty and causing a global turn to authoritarianism and chauvinism. Mainstream elites and political parties no longer have the answers. The populists and demagogues who fill the void don’t have a clue either, but what they do have is the snake oil of scapegoatism, and the salesmanship to hawk it effectively. I’m going to argue that current policy discussions underestimate the ingenuity and resilience of these merchants of hate. Most of my presentation will be devoted to deconstructing the methods. Normatively, my work is fueled with disgust and alarm at these unscrupulous political actors who don’t care about the harms they’re causing to society, and especially to historically marginalized groups.

Yet, I think we can’t afford to indulge in moral outrage. We can only push back effectively if we have a clinical understanding of what we’re up against. I’ll suggest that once we do this, we’ll see that there’s only so much that speech interventions can do. We should focus more instead on protecting and enhancing substantive equality. I say this not because I’m a free speech fundamentalist, but because speech restrictions may have very limited benefits and may even backfire, as I’ll try to show. Like my book, this presentation is going to explore cases from various parts of the world but I will end with a couple of questions and concerns I have about the American situation, which I hope you will help me answer. With those preliminary remarks out of the way, let’s plunge in.

I’ll relate what I have to say about hate to current concerns about fake news, hoaxes, disinformation operations, which is the topic that is impossible to avoid these days. I can’t recall, in fact, any communication related concern that has so dominated the global agenda. This attention, I think, has been a mixed blessing. On the one hand, it is good to see my research area of hateful disinformation being placed near the top of the agenda around the world. On the other hand, there are signs that we are approaching something of a moral panic.

There’s a tendency to overreact to certain salient aspects of the problem, to ignore other aspects that may be more important. To rush to judgment before the evidence is in, and to opt for quick, legal fixes to assuage the public’s sense of anxiety. We do need to respond to the urgent and critical challenge of disinformation campaigns, but avoid knee jerk reactions that solve nothing, while creating their own sets of problems. We should start, I think, by looking at how hate actually works on the ground. Sadly, there is no shortage of material to deal with. We know that every crime against humanity has been facilitated by hate speech, whether it’s European colonization of distant lands, or ethnic cleansings of native populations, or slavery, or apartheid, or genocides.

The process starts with one of the essential requirements of all collective action, which is the social construction of a “we,” a common identity. Any in-group requires an out-group, conjuring up a contrasting other. This could be as innocuous as Canadians defining themselves as not American. But things get less benign when the out-group is scapegoated for genuine grievances being suffered by the in-group. This is a politically attractive move because it is so much easier than actually addressing the real causes of a society’s problems. The out-group starts getting described in dehumanizing ways, often being compared to animals, for example. This can escalate into what the Rwandan Genocide Tribunal called accusation in a mirror, which is convincing the in-group that it is the victim here. That the out-group is really the aggressor that might strike at any time.

This heightened state of fear suspends people’s sense of justice and even their basic humanity such that when the final call to action comes, that they’re already primed to discriminate against or even physically attack their neighbors, co-workers and friends. Compared with a generation ago, we understand this process pretty well, and our antenna are sensitively tuned to the racist tropes, and the subtle othering contained in hate speech. What is less well understood, and which my book explicates, is the complimentary strategy of manufactured indignation, of deliberate offense taken in pursuit of political objectives.

The archetype is the reaction to the cartoons of the Prophet Muhammad published in Denmark in 2005, when protests rose against an allegedly intolerable insult. This case stood out for its transnational character, and its disproportionate violence. But at the local level, this strategy is in fact extremely common, and can be deadlier than and as outrageous as transnational Islamist attacks like the Charlie Hebdo killings, even if much less publicized because in many of these cases, the victims are not White. Intolerant movements routinely agitate against the release of books and films, the building of places of worship, or what unpopular minorities eat or wear.

The literature on progressive social movements helps us to understand their methods because although they lie at different ends of the political spectrum, there are structural similarities between progressive movements and hate groups. First, there is long-term investment in injustice frames. A narrative of struggle against historical adversaries. Second, there’s the curation of more transient injustice symbols, usually asked by others that can serve to highlight how the group is once again being victimized. So, this is, for example, a move from the description of Muslim minorities as being subjugated by the imperialist west, and then the use of these offensive cartoons as an injustice symbol that highlights or that is an example of this larger injustice frame.

Third, activists whip up outrage arguing that a line has been crossed, and fourth, they instigate protests, demand censorship, and acts of vengeance. The goal here is to assert their values, attract attention for their cause, put opponents on the defensive, all the while playing the victim role. So, I argue that the literal or instrumental demands that they’re making for censorship are really actually not important. The strategic objectives of assertion of values, for example, is really what’s at stake. These eruptions of mass offended-ness are presented as authentic expressions of righteous indignation but if they are of certain scale and duration, I dare say that they’re practically guaranteed to be orchestrated by political actors for reasons other than the defense of what’s sacred or even for the interest of the masses in whose interest they claim to act.

So, it’s this twin strategy of incitement and indignation, offense giving and offense taking that I call hate spin. My book looks at the use of hate spin by the Islamophobia industry of the religious right in the US, Hindu nationalism in India and hardline Islamist groups in Indonesia. These are the world’s three largest democracies. All three were constituted as secular republics. All three have a dominant but different religious community, and in all cases, despite their foundation as secular republics, they’ve always included religious nationalists pressing for the rule of identity over the rule of law.

International human rights law recognizes the need for state intervention against hate speech, or more precisely, incitement to harms against racial and other groups. So, Article 20 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights says, “Any advocacy of national, racial, or religious hatred that constitutes incitement to discrimination, hostility or violence shall be prohibited by law.” The European Convention on Human Rights as well as domestic laws in Canada and Australia, for example, contain similar bans on hate speech, or more properly incitement. The United States, of course, is an exception in the democratic world. Within public discourse, only incitement to imminent violence may be punished by the state. In practice, the threshold is so high that in effect hate speech in public debate is protected by and large under prevailing First Amendment doctrine.

But although there is a big body of literature, endless debates comparing American and European jurisprudence on hate speech, if you take a step back, and consider the global setting, I think you should in fact view the American and European approaches as more similar than different. This is really a petty family quibble. Their common liberal standard is to allow state intervention only for incitement to objective harms. Offending people’s feelings cannot in and of themselves be treated as criminal acts, even if it insults people’s deeply held beliefs. So, this is the common liberal standard across Western Europe, North America and Australia for example.

However, many countries outside this liberal orbit do police offense. Various kinds of insult law try to protect communities from expression that offends their identities. These include blasphemy laws used in many Muslim countries, and laws against the wounding of racial and religious feelings, which the colonial authorities planted in India, and are common throughout the British Commonwealth. This is Singapore’s version of an insult law copied from Indian law, which I’ve been trying to push my country to repeal, obviously with no success.

It says basically that, “Whoever intentionally wounds the religious or racial feelings of another could be jailed for up to three years.” So this is an offense law. Unthinkable in liberal democracies. But this exists practically word for word in Indian law, similar legislation exists in Malaysia and elsewhere. Blasphemy law, that is common throughout the Muslim world, would be similarly sweeping. So, there’s this major ideological divide between the more liberal societies that will only prohibit objectively harmful speech, if at all, and the rest that also want to criminalize subjective offense. But I think we should not exaggerate the difference because we are only talking here about the law, and not about other kinds of speech regulation.

We know that in the US, while the state is highly circumscribed in its power to interfere in public discourse, private actors such as universities, media, internet platforms may respond to social norms and pressure groups in ways that are, in fact, reminiscent of state intervention. They can suppress viewpoints, punish speakers by taking away their livelihoods, or their ability to participate in public life. Furthermore, the boundary between subjective offense and objective harms is not as clear as the law or my earlier graphic suggests. Because at what point does mere insult cause such psychological harm to people’s dignity that society needs to intervene? So, in fact, the question of where to draw red lines is a live issue within liberal democracies as well as between different political regimes.

Alarm about online disinformation seems to have made western democracies far more amenable to discussing state regulation in policing these lines. There is, I think, much less faith now in the marketplace of ideas, and business as usual is not seen as an option. But I think any intervention needs to be grounded in an empirical understanding of what we are actually up against. That, I think, is what is lacking in current debates. Let me try to highlight three gaps in our understanding. First, hate propagandists are not as dependent on digital media as conventional wisdom suggests. Conservatively, I’d say that three quarters of conferences on the topic, books, journals, special issues that examine disinformation are focused on the internet.

But so much depends on how we frame the question. If we start by asking, “Does the internet help hate groups?” Of course the answer is going to be a resounding yes. But if we instead ask, “How do hate groups work,” we actually get a subtly but I think importantly different answer. We’d realize that hate propagandists are not in fact going to be deterred if we deprive them of their internet toys. In many countries, talk radio, charismatic cable TV hosts do more to create intolerant eco chambers and filter bubbles than social media do. Face to face interaction within places of worship and study groups probably play a bigger role than online messages in cultivating religious intolerance.

Take, for example, one of the most controversial hate crimes in India of recent years. A landmark case in the Hindu Right’s so called Cow Protection Movement. In 2015, a lynch mob killed a Muslim villager in Dadri, Uttar Pradesh, after they were told that he had stolen a calf for his family’s consumption. Now, this mob didn’t require WhatsApp or Twitter, or any media for that matter. It was triggered by an announcement in the local temple.

Certainly, social media platforms are currently too hospitable to disinformation. Their speed, virility and anonymity are being exploited to the hilt, and it’s true there’s a knowledge gap that research needs to fill. But the problem I think with the disproportionate attention being paid to social media is that it places undue faith in techno-legal solutions. Second, I think existing and proposed measures against hate speech and fake news seem to be working with inaccurate conceptual models. They assume that we are dealing with discrete self-contained hateful messages that can be shot down sniper-like by prosecutors, moderators, fact checkers and other regulators.

But that is simply not how the most harmful hate propaganda works. Instead, it takes the form of highly distributed multi-model, multi-message campaigns. What the public relations and advertising industries call integrated marketing communication. In the US, fortunately, you do have hate watch groups and other think tanks that have been studying these networks in detail.

https://player.vimeo.com/video/307521176

These networks are made up of different types of actors. Many of them try to normalize discriminatory thinking by sounding as reasonable as possible. They insert their ideas into an online space where they benefit from being in the company of more mainstream sources of information. One scholar has, I think, quite usefully described this as a kind of information laundering where corrupt messages, black market messages, if you will, are circulated along with more legitimate credible information until we can’t see the difference. Rhetorically, these campaigns are often embedded in grand narratives, often invoking a golden age as well as past injustices and traumas. They are refreshed with contemporary examples to keep the community in a state of heightened and constant anxiety.

When the community needs to be activated to take part in a riot or to support discriminatory legislation, for example, activists simply need to point to some new development as the last straw. The audience’s preloaded memories do the rest. Some governments including in Singapore are pushing for regulation against online falsehoods, and it’s true that lies are part of the stock and trade of hate propagandas. But the messages can also deceive without being untrue. Selective curation of factual news stories about crimes committed by minorities, for example, can create unwarranted fear of these groups. This is a well-known tactic of White nationalist groups in the US, and it’s also being done by the far right in Europe.

These, for example, are selected images from the refugee propaganda being propagated by White nationalists in Europe. It is fueled by curating news reports of people with Muslim sounding names suspected of sexual offenses.

Each individual report may be factually true, but the lie is in the very selective curation, exaggeration until it creates this overwhelming fear of minorities being sexual predators. The division of labor means that it is extremely difficult to hold accountable the leaders who ultimately benefit from the campaign. The most extreme and shocking expression is usually left to low level activists and anonymous trolls. The leaders themselves avoid inflammatory language or indulge in so-called dog whistles, and thus claim plausible deniability.

The politicians like Donald Trump and Narendra Modi in India show their true colors when they refuse to condemn extreme speech and hate crimes by their followers. But the problem is that while their silence is morally reprehensible, this is not something that can be legislated against. Third, hate merchants, I argue, are adept at weaponizing the laws and regulations designed to contain them. This is especially the case with the insult laws that I mentioned earlier. Governments claim they need such laws, including against blasphemy, to maintain social harmony. But these backfire badly. When the state declares blasphemy as a crime, fanatical groups feel justified in exercising vigilante justice and mob vengeance against the perceived offense. Or after vociferously taking offense at a film or book, they demand that the state enforce its insult laws.

Why shouldn’t they, since offense is technically a crime? Thus the coercive capacity of the state gets hijacked by the most intolerant groups. Instead of promoting respect for diversity, these laws encourage competing radical groups to express more and more outrage at anything that is too different for their liking as a political strategy to trigger legal action against their opponents. The most reasonable religious groups are sidelined by this dynamic. Even though their peaceful methods, their belief in inclusiveness and moderation is exactly what society should incentivize. But they’re sidelined, and instead, the law promotes more extreme offense taking.

When these groups are themselves targeted by the law or by protests, hate agents use their bigger opponents’ strength to their advantage. They play the victim to milk their community’s sympathy. Thus they gain political mileage even when they’re called out, countered or regulated. When the liberal media accuse them of racist speech, or when they’re blocked from speaking on campuses, they flaunt these actions to their supporters as evidence that the system is against them. This has been the response to recent private and public efforts to clean up the internet. So, internet giants, for example, have been accused of siding with the Muslim Brotherhood. Germany’s net enforcement act, the NetzDG Law, has been labeled by the far right AFD party as politically motivated censorship.

In this refugee cartoon, you can see caricatures of Angela Merkel and Barrack Obama silencing the victim of a gang rape with their political correctness. This is a common trope in far right propaganda. We can think of these counter responses as a variation of the non-violent protest strategy pioneered by progressive movements called political jujitsu, which is about absorbing the opponent’s blows and using their energy against them. Although in 2018, we should probably update the analogy. Let’s not call it political jujitsu, let’s call it “vibranium politics.”https://player.vimeo.com/video/307104154

So, I think we have to picture hate merchants as highly skilled spin doctors in vibranium suits. Smart, creative protests, these techniques are not the preserve of left wing progressive groups. Social movement theory tells us that the repertoires of contention often transfer among unrelated movements. So, really, it shouldn’t surprise us to see hate groups learning from the very people they despise. This is probably most obvious in the aesthetics of hate propaganda. It used to be the case that neo-Nazis would confine themselves to a retro look, copying the visual signature of 1930’s national socialist propaganda. Nowadays though, to appeal to millennials, they draw from a much broader stock of graphic traditions, including the left.

In addition, their public facing websites are designed to look professional, corporate, authoritative, aiding the process of information laundering. Every year, the highly coveted Effie Awards are given to advertisers and agencies to recognize all forms of marketing communication that contribute to a brand success. If hate groups took part, I think they would give the likes of Unilever and PepsiCo a run for their money. A gold Effie Award for hate marketing must surely go to … no, not to Trump; to India’s Sangh Parivar movement led by the Hindu chauvinist organization, RSS, and Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

Next to them, Trump is an amateur. Consider one of the Hindu rights’ long running disinformation campaigns. It’s called the love jihad. It sells the idea that Hindu families are being threatened by Muslim conspiracy to steal away their daughters and forcibly convert them to Islam. Through this grassroots subterfuge, India’s 15% Muslim population will supposedly take over control of the country from the 80% Hindu majority. The unstated macro-strategic objective of this propaganda campaign is to unite Hindus behind Narendra Modi’s Hindu nationalist party, the BJP. Now, this task of uniting the Hindus has never been straightforward because this is a group that currently numbers one billion. They’ve always been divided along caste, class, language, regional lines.

The BJP in contrast, is an upper caste, Hindi speaking and northern Indian party. So, it doesn’t take a marketing genius to realize that the construction of a Muslim other is essential for the BJP’s electoral success. But this has always been easier said than done. Of course, Muslims are not fresh off the boat aliens in India but intimately integrated into Indian culture and society. Bollywood is full of Muslim-Indian stars. Unhelpfully for Hindu nationalists, there is no homegrown Muslim terrorist threat in India. But Indian families are gripped by a more domestic form of insecurity. A profound fear that their children will marry outside their communities. It’s a fear that is frequently expressed in disproportionate, even murderous rage.

Now, most of these taboo relationships are actually within the Hindu community. Relationships crossing caste lines are mathematically more probable than inter-religious romances. But there are sufficient numbers of Hindu-Muslim liaisons to whip up into a moral panic. The love jihad theory is something conservative Hindu families want to believe because it requires no soul searching. They don’t have to confront the truth as old as time, that the heart wants what it wants, that society is changing, that some traditions are no longer relevant and that parents should just chill. So, this is something that the Hindu right can work with. It is fertile ground for them. The love jihad conspiracy is strenuously marketed.

It has given families and community leaders the excuse to break up consensual marriages, lynch Muslim men, force brides to return home. Let me just momentarily draw your attention to the bottom of this poster. You’ll see the hotlines. Even that very simple act, what marketing genius. Imagine if you walked around campus, or walk around town and you subtly started noticing these posters that said, “Is your iPhone overheating? Call 1-800-FONE-ONFIRE.” There might not be anything wrong with your phone, but I guarantee you, you’ll start to get nervous. This is precisely the tactic that’s being used here by putting these hotlines all over India. “Is your family a victim of the love jihad? Call this hotline.”

Its political utility surfaces during election campaigns when alleged love jihad incidents have been amplified by activists, and used to instigate communal violence and solidify the Hindu vote bank. Investigations into the causes of the worst riot in the run-up to the 2014 general election, in the critical state of Uttar Pradesh found many villagers referring to love jihad. But I don’t want to leave out the US, so I’ll give a consolation price to an American campaign that deserves special recognition for how effectively it has secured the holy grail of earned media, as marketers call publicity that they don’t have to pay a lot for. The client is the American Islamophobia industry and the creative director of this campaign is a lawyer, David Yerushalmi. He calls his strategy Lawfare, basically legal warfare. So, here’s what he says about it.https://player.vimeo.com/video/307521067

“Lawfare is one of the most effective tools both in terms of changing law, changing policy, changing behavior and also for purposes of public relations because nothing grabs the attention of the media more than a battle in court with a drama of courtroom narratives and testimony.” –David Yarushalmi

I think his final point is actually the primary strategy. So, a statement by The Center for Security Policy in a 2015 publication says quite transparently that Lawfare presents an opening to influence and shape public discourse, and ultimately shape public opinion precisely by using the forum and procedures of the court to get a platform for their ideas.

One nationwide Lawfare push is the anti-Sharia law campaign. Yerushalmi crafted proposed legislation or amendments to state constitutions to protect states from an alleged Muslim plot to introduce Islamic law into America. A completely fabricated threat. But since 2010, more than 200 anti-Sharia bills have been introduced in 43 states. Only 14 have actually been enacted. In Pennsylvania, I understand it never got out of the committee stage partly because of a firm pushback by an interfaith coalition that saw through its discriminatory intent. But that’s not to say that the campaign was defeated. Getting legislation passed was never the point. The idea was to inject the Islamophobia industry’s talking points into legislative chambers, and in wider public debates through ballot measures, thus normalizing bigoted ways of thinking and feeling about Muslims.

Another Lawfare campaign involves buying advertising space in public transit systems for anti-Muslim messages. Now, thankfully, more metro operators have been unwilling to allow such advertising. But when they try to refuse, the activists take them to court claiming that their First Amendment rights have been violated. To avoid unconstitutional viewpoint discrimination, Washington DC’s metro had to resort in 2015 to banning all issue oriented advertising. One case was just concluded in Seattle last month where the Ninth Circuit Appeals Court, is that right, Ethan? Yeah? The Ninth Circuit Appeals Court finally ruled in favor of this campaign.

So, they are allowed to go ahead with advertising. When the lower court had sided with the metro operator this is what Pamela Geller, one of the chief Islamophobia activists, had to say. She makes fun of the courts, accuses government authorities of submitting to Islamist supremacists’ demands. So, the moral story here is, either way, they win. The court sides with them, you win. The court rules against them, you also gain propaganda advantage.

Another outrageous campaign targeted a small Muslim community in middle Tennessee, which announced plans to build a mosque in 2010. The national Islamophobia network rolled in, organized protests, tried to stop the project through the courts. The opponents of the project said that Muslims do not qualify for religious freedom protections because Islam is not a religion, it’s a violent political ideology. Eventually, of course, this argument was thrown out. But for a while there, by taking the issue to court, the activists succeeded in gaining mainstream media platforms for this outrageous assertion that Islam is not covered by the Free Exercise Clause of the First Amendment.

So, again, the movement wins even when it loses. It’s when you look at such formidable hate campaigns here and around the world that it becomes clear that current policy debates are just not keeping up. They are too focused on how to fix the big internet problem, how to deal with individual messages, whether it’s fake news or hate speech, and not examining how these things work. I think we need to recognize that trying to suppress offensive speech backfires, and even if we try to regulate incitement, which is necessary, it’s rarely effective.

I’m hearing this point being echoed by human rights defenders who are dealing directly with the problem. They tell me we’re focusing too much on speech, not enough on substantive equality. Let’s recognize the limitations of speech policy, and instead devote more attention to creating and protecting anti-discrimination regimes. I think this is actually one of the strengths of the American system, and it accounts for the confidence that successive waves of immigrants and religious minorities have in the constitutional order. Will it survive the Trump presidency? Here’s what someone told me a few weeks ago in Philadelphia. “Trump in the end cannot do whatever he likes because in this country, we have a separation of powers.”

The person who told me this was my Lyft driver, Sabir, who arrived from Afghanistan 14 years ago. This was his answer when I asked him whether it was hard being a Muslim in Trump’s America. His response reminded me of conversations I had with Ossama Bahloul, the unfortunately named Imam in Murfreesboro, Tennessee, who had faced the full brunt of the anti-Muslim hate groups when he and his congregation wanted to build a mosque. They had to endure more than a year of vile hate speech. It was to me an illustration of what critical race theorists have always said about that old adage that hate speech is just a price we have to pay for free speech. The problem is the price is never paid equally. The cost falls disproportionately on vulnerable communities.

So, I wondered, why should Muslims in Murfreesboro have any faith in a society that allows such vilification to go unpunished? Now, Imam Ossama’s answer was that the constitution was on our side, and he was right. At one point, the mosque opponents succeeded in pressuring Rutherford County to stall the project, but then the Department of Justice stepped in. Ossama recalls going to the federal district court in Nashville for a hearing. It was his very first time in an American court, and there he hears the US attorney describing the case as the United States of America versus Rutherford County. It dawns on him that the USA was him, an immigrant from the Middle East. Imagine the impact on a new immigrant to know that the Constitution works for you.

The mosque project was delayed, but finally completed, which is a much happier resolution than similar disputes in other countries. My book also tells a story of a mirror dispute in Indonesia, where small Christian congregations’ attempts to build their churches have been obstructed for more than 10 years by hardline Muslim opposition. They’ve taken to organizing services in the open air outside the presidential palace just to remind the president that their case still hasn’t been resolved. I’ve given talks in Indonesia, and relate to them the happy ending in the Bible Belt in America. Most Indonesians are stunned, they can’t believe it because the US is most famous for its uncompromising stand on liberty and free speech, which is assumed to impose a very heavy cost on the dignity of religious communities.

But much less well known around the world is America’s equally firm and exemplary stand on religious freedom and equality. Sometimes I wonder now though whether Americans know this themselves, that this, in fact, is one of the strengths of the system. But we’ve come to query America, not to praise it. So, I want to end by sharing some doubts and concerns that I have about American responses to the current divisiveness.

First, will America transcend the tribalism rather than simply replacing right wing intolerance with left wing intolerance? To borrow legal scholar Robert Post’s terms, the American Republic isn’t constituted as either a single community, or as a bunch of separate communities. It’s supposed to be a community of communities. So, I wonder, who’s building this community of communities right now? Obviously not the political class, which is too entrenched in partisan politics, but is civil society picking up the slack? I don’t see it, but perhaps it’s happening under the radar, at the grassroots. You tell me. Or maybe it will happen after the left wins. In the best case scenario, maybe the left will follow in the footsteps of Nelson Mandela who transitioned from militant to peacemaker when victory was finally within grasp. Or is the left content with an interminable war? I don’t know.

Second, we think of societal norms as a softer mode of speech regulation than law. The historian Timothy Garton Ash has observed that what makes liberal democracies liberal is not that they don’t sort good speech from bad speech, but that the sorting work is done as far as possible through moral suasion rather than law. He describes two styles of regulation, not as opposites but as points on a continuum. Think of social norms as water and law as ice. Two states of the same matter. Extending Garton Ash’s analogy though, what if the water isn’t like the gentle currents nudge us in a particular direction, but water cannon that knock us off our feet?

When protesters are able to impose prior restraint on speakers, when they can cause writers to lose their livelihoods, when editors and publishers act more out of fear of the public than out of professional responsibility, have things gone too far? Elsewhere, such pressure is associated with the right. I think what’s distinctive about the US, and in fact, that’s what I hope to figure out by the end of my short stay here, is this unusual circumstance that this pressure’s exerted as much by the left as by the right, allowing the right to gleefully claim that their opponents are the ones who are intolerant of difference. Is the left content with this? What exactly is the game plan here? I don’t get it.

Third, where is civic education in the US going wrong? How can it be made right? We know that the practice of democracy requires not just formal democratic institutions, but also a democratic culture. What are we to make of the fact that the country with the longest unbroken record of constitutional government still hasn’t had time to entrench that democratic culture? If so, what hope for everyone else? Civic education by schools, media, civil society and state was meant to inculcate values like equal rights and reciprocity, and thus inoculate citizens from the influence of demagogues and hate groups. Even lessons from one’s own history, which in the past, inspired great civilizing moves, seem to have a limited shelf life of one or two generations.

After a couple of generations, it seems that the old mantras like Never Again are no longer felt in people’s bones. They become empty slogans. Maybe the cycle just has to be repeated along with the inhumanities of the past. Perhaps society’s better angels will only surface after we go through hell. If so, the sober prognosis may be that as bad as things seem to be today, they have to get worse before they get better. Discuss. Thank you.

Cherian George is Professor of Media Studies at the Journalism Department of Hong Kong Baptist University, where he also serves as Director of the Centre for Media and Communication Research. He researches media freedom, censorship and hate propaganda. He is the author of five books, including Hate Spin: The Manufacture of Religious Offense and its Threat to Democracy (MIT Press, 2016). He received his Ph.D. in Communication from Stanford University. Before joining academia, he was a journalist with The Straits Times in Singapore.